I am excited to announce this week the publication of a scientific paper that I have been working on. The paper is quantitative in nature, so it does not contain any new fossils to report. However, it does report, I think, some important results relating to the extinction of dinosaurs and the survival of birds at the end of the Cretaceous.

Whether dinosaurs went extinct quickly or over the course of millions of years is still a matter for debate. Our study looked at change in tooth shape in small maniraptoran dinosaurs, relatives of Velociraptor including toothed birds, over the last 18 million years of the Cretaceous. We found no evidence of a long-term decline, suggesting they became extinct suddenly.

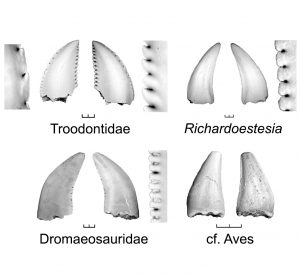

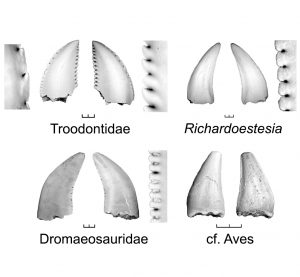

Maniraptoran Teeth

This image depicts representative teeth from the four groups of bird-like dinosaurs (including toothed birds) analyzed in this study, with enlarged images of tooth serrations. Scale = 1 mm.

Photo credit: Don Brinkman. Modified from Larson et al. 2010. Can. J. Earth Sci. 47: 1159-1181.

A larger question, is why these bird-like maniraptorans became extinct suddenly while their close relatives, modern birds survived the extinction event. We put forth the hypothesis that it had to do with dietary specialization. Looking at the diet of modern birds, you can reconstruct what sort of diet the ancestral toothless modern bird might have. Those data suggest that the ancestral bird was at least partially granivorous, able to eat seeds. The sharp-toothed maniraptoran dinosaurs wouldn’t have been able to eat seeds efficiently, specializing instead mostly on animal remains. During the severe ecosystem upheaval at the end of the Cretaceous, food would soon become scarce for meat-eaters, but abundant seed stores, that could last for years, would have provided enough nutrients for the ancestors of modern birds to survive.

So as not to repeat too much ground from press coverage and other online information covering our paper, I thought this would be a good opportunity to highlight an important part of the media process involved in a palaeontology paper: the creation of artwork. To accomplish that, I’ve asked the Royal Ontario Museum’s Danielle Dufault, the artist that worked with us on this project, to answer a few questions about the artwork she created.

1) For those who don’t know, could you describe the process of creating one of these reconstructions?

The first step of creating such a piece is, of course, to understand what the illustration needs to represent. As this is going to be the face of a scientific paper, it has to communicate the research in a glance that is both informative and captivating, because the entire purpose is to draw a potential reader in further to earn more about the work it represents. So step one is to learn all about the science it represents and what aspects of it the authors want to broadcast most poignantly. From there, I come up with a few thumbnail sketch ideas of how the idea might play out and what elements can be present. When the composition is roughly agreed upon, the details can begin taking shape! Researching what species of flora and fauna were present in the environment is important, so lots of background reading is involved with these reconstructions. When species are all agreed upon with the authors, I seek out the most current research on their subjects to try and represent them as closely to what our current understanding of them can depict. Paleontology is a science in which new discoveries are made all the time, so our idea of what something might have looked like can change drastically and quickly!

Early draft of reconstruction. Image credit: Danielle Dufault.

I refer to lots of photo reference of what an environment can look like under different conditions, and build big reference folders. There are so many analogs today that can serve as really good reference for what we no longer have. Things like colours and patterns are fun to play with and can serve to direct attention, but also to indicate how an animal lives, so this also all goes by the authors for approval, often with several iterations! So after all this research it’s paint-paint-paint…or draw-draw-draw. I work mostly digitally so call it however you want!

2) What were some aspects of the piece that you or the authors wanted to highlight and how did you go about highlighting them?

The big twist that this new research suggests is that there may have been small avian theropods who may have survived the Cretaceous extinction by eating seeds, which could have certainly remained as a food source even through massive ecosystem-razing fires that would have destroyed most food sources. So the idea here was to present this, small, ground-dwelling, seed-eating bird in a Late Cretaceous environment, along with the incredible diversity of theropod dinosaurs it was likely coexisting with.

3) Using forced perspective was an interesting choice for the work that seemingly isn’t very common in reconstructions. Why did you decide to use that method?

I really wanted to try and depict the scene for the level of this little survivor, who is not only making the best of shelter to avoid predation, but also making the most of his available food source! All of the dinosaurs in this scene are relatively small-bodied, and I wanted to try and make people think for a moment that some of the best stories to be told about dinosaurs aren’t just about the giants who rumbled the earth beneath their feet. This is a story about a little guy who got away against incredible odds, because he didn’t share the features of dinosaurs that make them almost mythical to us! He is familiar to what we know in today’s dinosaurs, and with that idea, he’s our eyes into the Cretaceous scene in the Hell Creek, a big and beautiful world at the end of it’s time.

4) What aspect of the piece did you find the most challenging?

Fitting so many animals into one scene is a real challenge that I haven’t done much of! Creating an interesting composition that doesn’t look like an overstuffed sticker-book is actually quite difficult, so I tried to play a lot with atmosphere, perspective, and the environment to create enough “space” for these animals to all be existing comfortably and believably.

A more detailed depiction of the final artwork with the major design elements in close to their final form. Artist Credit: Danielle Dufault.

5) What is your favourite aspect of the piece?

I love that this one is all about the little guys, and giving them their due respect! Big dinosaurs take the limelight most of the time so it’s fun to take a look further down to the ground and be just as awestruck. It was incredibly fun to depict all these different evolutionary experiments that the theropod lineage took, because there was so much more than we have today! Showing them being so dynamic was incredibly fun.

6) What do you hope people will take away from the piece?

Big, powerful, and scary doesn’t always equal success. It did for a time, and the dinosaurs had a good run. Take it from this little survivor who went on to repopulate the world with modern birds like we have today.

For more information on this new publication, you can check out our press release on the subject and the publication itself over at Current Biology. You can also find more information by my co-author Caleb Brown on the Royal Tyrrell Museum’s blog. That’s all for now. Talk to you again soon.

By Derek Larson