By Lindsay Kastroll, Master’s student in Biological Sciences, University of Alberta

Demystifying the way the science actually works…

Welcome back to Palaeo How-To! In the last few posts in the series, we covered types of fossils and how they form. This information lays the foundation for the next important concept in palaeontology: how are fossils found to begin with? I hope you like rocks, because we’re going to start with a crash course in geology.

There are three types of rocks in the aptly named rock cycle: igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary. Each type forms in a different way. Igneous rocks are formed by cooling lava (on the surface) or magma (underground). Metamorphic rocks are formed when preexisting rocks of any type are subjected to extreme pressure and heat when buried deep underground. Sedimentary rocks are also made of preexisting rocks, but rather than being transformed by pressure and heat, older rocks erode down to tiny grains which then accumulate and solidify together. You can also get sedimentary rocks that form from the precipitation of minerals in water, but that’s neither here nor there.

Fossils are typically only found in one of these rock types. I’m going to do the professorial thing and ask you to think about which one that might be.

Metamorphosed leaflets of the extinct fern Pecopteris from the Sam Noble Museum. The leaflets seen on the left side of the image are in their normal shape and size, but those seen on the right side are sheared and stretched.

If you said sedimentary rock, you would be correct! Fossils are made in sediment: trace fossils typically form when impressions in the loose sediment solidify, while body fossils need to be buried under sediment. Fossils generally cannot be formed in igneous rock, because the heat of crystallizing lava would destroy them. Volcanic ash is a gray area: rocks made from the ash are technically both sedimentary and igneous, and any organisms that were buried beneath it are typically well-preserved. While fossils can be found in sedimentary rocks that are undergoing metamorphism, the geologic processes driving this transformation tend to alter them significantly, and may ultimately destroy them with intense heat and pressure.

One of the cool things about sedimentary rocks is that they are deposited in layers, with new layers forming on top of old ones. This means that, unless metamorphism has folded the layers in a really weird way, you can use their vertical positions to judge the relative ages of the fossils they contain (in other words, fossils in lower layers are older than those in higher layers). Determining a sedimentary rock’s precise age in years is difficult, though, because all of the grains of sediment in a sedimentary rock have come from the erosion of other, pre-existing rocks. This means that any date that you could determine based on those grains would actually be older than the rock itself. And we can’t use the most well-known form of radiometric dating, carbon dating, on most fossils because after tens of thousands of years the carbon that they originally contained will have decayed too much to be useful.

In that case, how are fossils that are millions of years old dated? Unfortunately, it isn’t very precise. One way is to date the nearest igneous rock layer (since igneous rocks crystallize directly from cooling lava/magma, they are rocks with their own “birthdays” that can be estimated through radiometric dating). Another way is to rely on commonly found fossils whose geologic ages are known, which are called index fossils. Index fossils are typically invertebrates or plants.

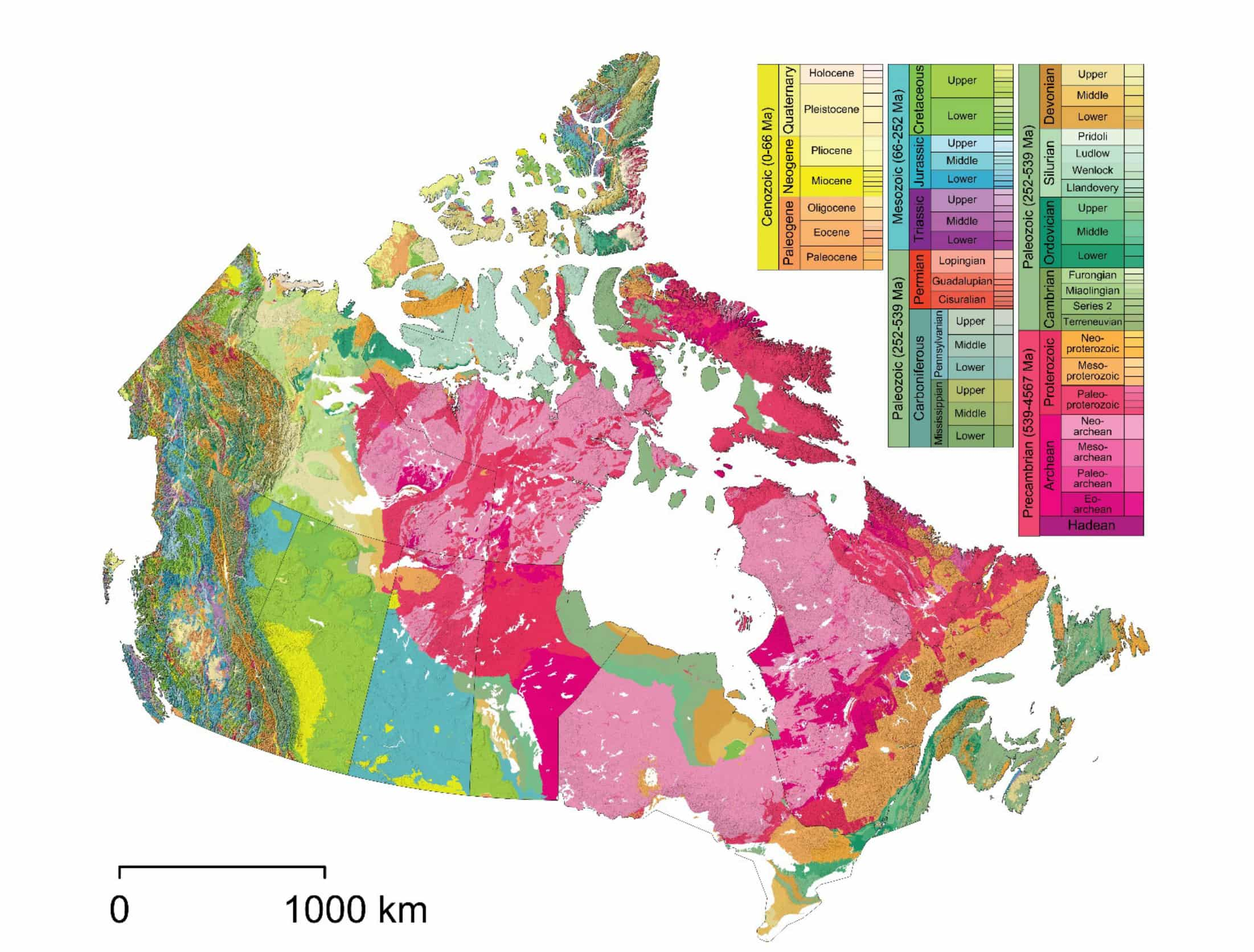

Geochronological map of Canada, showing the ages of rocks in different regions. Different provinces have different data sources and resolution levels, resulting in some abrupt artificial changes along provincial borders. 2024, Natural Resources Canada.

Okay, so we know the type of rock we are looking for, and we know we have to look for layers of the rock that are the right age… Now we can start prospecting. Prospecting is the act of going out and searching for something, most commonly minerals and ore. Palaeontologists use this word to describe looking for fossils. Theoretically, any sedimentary rock could have fossils in it; knowing the approximate age of the rocks and the type of sedimentary rock lets you narrow your search to specific species. For instance, if you were looking for stegosaur fossils, you would probably want to limit your search to Jurassic sedimentary rocks that formed in terrestrial environments as opposed to marine ones.

Palaeontological prospecting often means going hiking in remote areas to look for exposed fossils. In Alberta, that typically means hiking down into wet river valleys or traipsing through harsh badlands. Being able to recognize fossils takes practice: distinguishing between rocks and fossils based on properties like shape, texture and colour requires an experienced eye. I’ve heard stories of young palaeontologists meticulously excavating “dinosaur bones” that ended up just being pieces of coal. It happens!

When a fossil is found, it’s usually in pieces after being exposed to the elements. Often those pieces are falling out of a cliff face or hillside, and palaeontologists have to search for the source in the rock layers above and dig to expose the parts that are still in situ (in place). Sometimes there aren’t any more pieces, though: perhaps the bones were exposed for so long that they weathered away in the elements, or the skeleton broke apart during the Mesozoic and only a portion was preserved. Partial fossils can be difficult to work with, because they can be hard to identify to species. If particularly distinctive parts of the body happen to be preserved, it may be possible to confidently identify the specimen to a broad family group, or more rarely, to specific genera or species. Other times, the bones might be so fragmentary that they are impossible to work with, and some palaeontologists won’t even bother to collect them.

University of Alberta Master’s student Fatima Iftikhar climbing a steep slope to reach some mystery fossils in Dinosaur Provincial Park. You can see one shiny, sun-bleached bone exposed just behind her shoulder!

When we see a fossil exposed at the surface, we always hope that it’s intact, even if it is just an isolated bone, leaf, footprint, etc. The best case scenario, though, is that there are more fossils associated with the first one. Palaeontologists will often do exploratory digging around a fossil to hopefully expose more related pieces – in dinosaur palaeontology, we’re obviously looking for the rest of the skeleton. Oftentimes bones are isolated; they might have been washed away downstream while the body decomposed in a river channel, for instance. Other times a substantial amount of the skeleton is preserved, likely due to rapid burial after death. Unfortunately, skeletons are almost always incomplete to some degree: to get a complete skeleton, the animal would have to be buried extremely soon after death to prevent scavengers and other agents of decomposition from separating the bones.

When bones are preserved in the arrangement they were in during life, they are said to be in articulation – this is ideal, because we can learn a lot about how the animal’s body was configured and how it moved. When the bones are near each other, but not neatly arranged, they are said to be in association. We can often assume that associated bones are probably from the same animal, but that isn’t always the case. When several individuals are preserved together, we call the deposit a bonebed, and its fossil content a mass death assemblage. Mass death assemblages can contain the bodies of multiple species of animals, or sometimes many bodies of one species of animal. The Pipestone Creek Bonebed is of the second type, and is estimated to contain the remains of hundreds of Pachyrhinosaurus lakustai.

Okay, so now that we’ve talked about a little bit of the basics of fossil finding, what do you do if you think you’ve found a fossil? It can depend on the laws where you’re located. In Alberta, very strict laws protect fossils found in the province. Fossils found in a provincial park may not be removed under any circumstances unless you have a permit; outside provincial parks, you may only pick up a fossil if it’s lying on the surface, rather than embedded in the ground. If you have to pry or dig, that fossil can only be collected with a valid permit. Even legally collected fossils remain the property of the province and cannot cross Alberta’s borders; by legally collecting a specimen and taking it home, you are acting as a steward of Albertan natural history. That’s a pretty sick title, if you ask me.

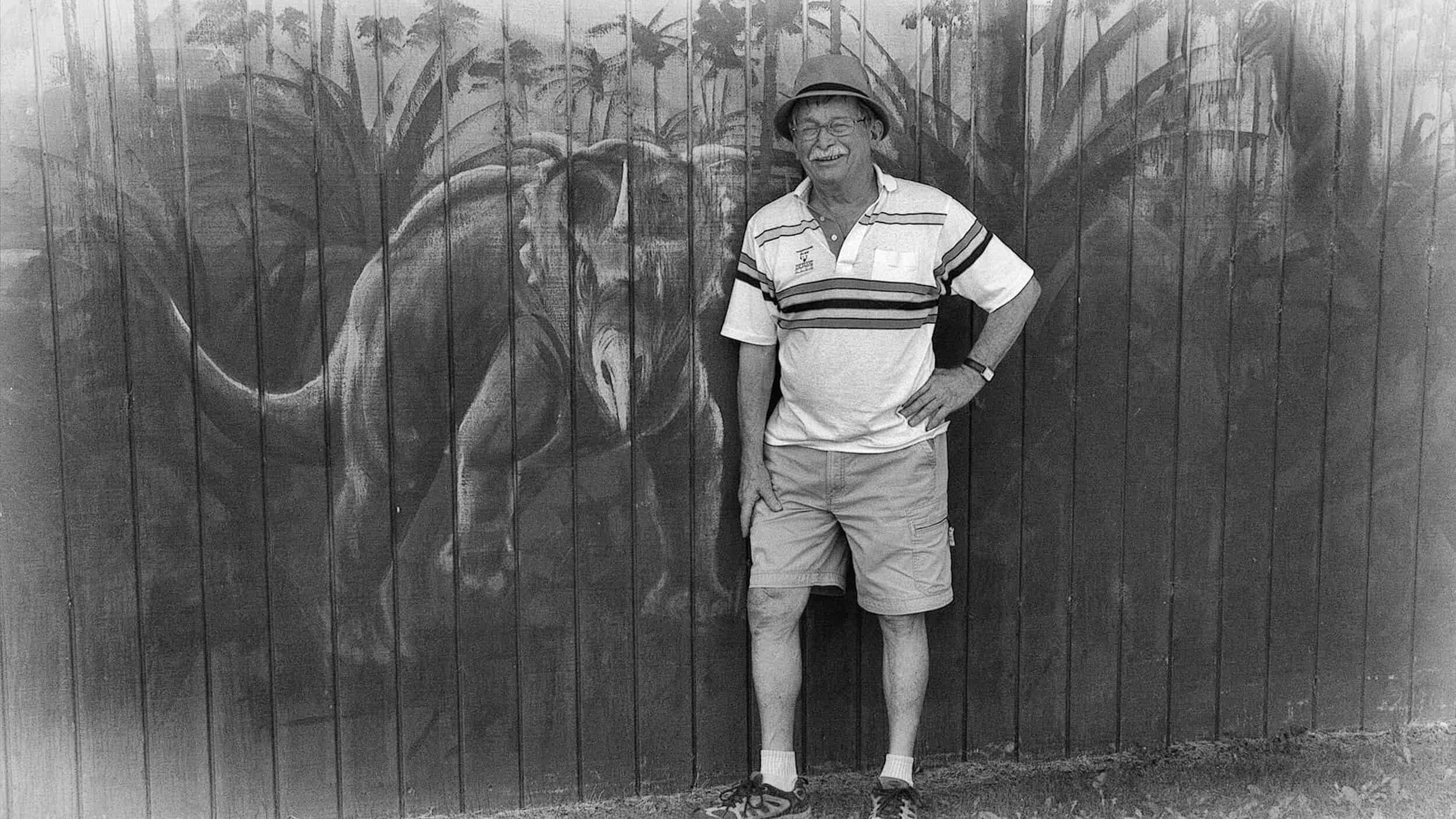

Grande Prairie high school teacher Al Lakusta discovered the Pipestone Creek Bonebed in 1974. The new species of Pachyrhinosaurus that was found there, Pachyrhinosaurus lakustai, was named in his honour! Photo from Follow the Bones.

If you think you’ve found a fossil of scientific significance, no matter where in the world you are, the best advice that I can give you is to leave it in place, take detailed notes about its location, and contact a palaeontologist. This is because the rock layers in which the fossil is preserved provide important environmental context, and if you remove the fossil with the intention of turning it over to a museum, that environmental context may be lost forever.

What do I mean by environmental context? Well, let’s circle back to sedimentary rocks. The type, size, shape, and orientation of the grains in a sedimentary rock can tell a geologist important information, like whether they were deposited in a desert, river, ocean, etc. They can even tell what direction the wind/water currents were flowing! Knowing the precise location of the fossil also allows palaeontologists to determine which layer the specimen comes from, helping them estimate the age of the specimen and making it possible to determine which other organisms are present in the same layer. This allows them to reconstruct the communities of plants and animals that lived alongside each other, as well as the habitats they lived in. All of this information could be lost if the palaeontologists aren’t able to access the original location where the fossil was found.

Once a fossil has been found, how do palaeontologists collect it? Well, to learn more, keep an eye out for the next Palaeo How-To!

✏ Email your Palaeo questions to info@dinomuseum.ca! ✏